Jump to:

- Identifying Aiptasia

- Which Anemone is it?

- The Biology of a Pest

- Distribution

- Habitat

- Morphology

- Behavior

- Feeding Habits

- Reproduction

- Methods of Removal

- Physical Removal

- Chemical Removal

- Natural Remedies

- Conclusion

Introduction

Nearly every saltwater hobbyist can tell stories of the hours spent looking at their new aquarium, watching to see what new life will emerge from the live rock. It’s almost a magical time, especially for the new reef-keeper, as the wonders of the sea slowly unfold within the small glass world we’ve created for it.

Most stories that involve Aiptasia anemones begin in the same way. Suddenly, a new little anemone is spotted on a newly added piece of live rock or live coral fragment, just a “baby”…

But soon that one “baby” becomes two, then five, then many more!

True to their name, Aiptasia anemones (which means “beautiful”) are elegant, but they are also invasive and aggressive competitors in the home aquarium. Left unchecked, these anemones will often totally overrun a saltwater aquarium.

Aiptasia anemones have developed to be survivors and are very opportunistic. They reproduce both sexually and asexually and are capable of regenerating an entire new anemone from just a small piece of themselves. Aiptasia are also capable of defending themselves.

When Aiptasia anemones are disturbed by either a passing fish, invertebrate, or even the hobbyist, they eject dangerous white stinging threads called acontia. These acontia contain venomous cells called nematocysts. Nematocysts are capable of delivering a potent sting that can cause tissue regression in sessile corals, immobilize prey, and even kill unlucky corals, crabs, snails, or fish.

Aiptasia anemones are considered by many saltwater hobbyists to be a pest in the saltwater aquarium. Early identification and action are required to quickly remove Aiptasia anemones from your aquarium before they reach problematic proportions. Once they reach a mature size and population in the aquarium, their control and removal are far more difficult.

Identifying Aiptasia

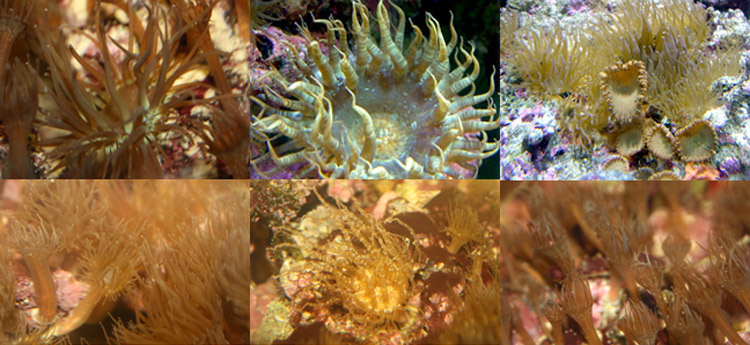

The first step to controlling an Aiptasia infestation is proper identification. It does little good to invest time and money into a solution to the wrong problem. Above are photos of various Aiptasia anemones.

Aiptasia anemones can be identified by their resemblance to miniature palm trees, with a polyp body (the coelenteron) up to 5 cm (2 in) in length and an oral disc up to 2 cm (3/4 in) across, bordered by a mixture of a few long and many short tentacles (up to 100 tentacles may be present) positioned in narrow rings on the outer margin of the oral disc. The tentacles are long, slender protrusions that form sharp points at their ends. Majano anemones can sometimes look like Aiptasia, but the main difference is that Majano anemones have rounded or bulbous tentacles instead of pointed ones.

At the center of the oral disc is the mouth in the form of an elongated slit. At the base of the polyp body is the pedal disc, which functions as an anchor for the anemone as well as a means of asexual reproduction.

Coloration of Aiptasia is due to the presence of zooxanthellae (microscopic photosynthetic dinoflagellate algae, family Symbiodiniaceae). For this reason, Aiptasia that live in well-lit areas of the aquarium are usually light greenish-brown to dark brown. Aiptasia in areas that receive less light are typically medium to light brown or tan in color. Aiptasia that live in low-light areas or areas without light can appear transparent or white. Often, an anemone’s column or stalk is lightly marked with parallel longitudinal lines. Sometimes white or light green flecks may also be present near the tentacles, and it is not unusual for juvenile specimens of Aiptasia to be entirely covered with them.

Like all members of the phylum Cnidaria, Aiptasia anemones have the ability to sting for both offensive and defensive purposes. All Cnidaria have stinging cells called cnidocytes, each of which contains a stinging mechanism, cnidae or nematocyst. Aiptasia possess both cnidocytes on their tentacles as well as specialized cinclides around the lower part of the column (small blister-like protrusions) through which they expel acontia.

Acontia are threadlike defensive organs, composed largely of stinging cnidocyte cells, which are expelled out of the mouth and/or the specialized cinclides when the Aiptasia is irritated. Many anemones do not have acontia or cinclides, but Aiptasia do.

The nematocysts of Aiptasia have a toxin that is more potent than the majority of corals kept by the marine hobbyist (with the Elegance Coral, Catalaphyllia jardine, being one exception) and can cause tissue regression in corals in your aquarium, immobilize prey, and even kill unlucky snails or very small fish.

As an added defensive mechanism, Aiptasia can also withdraw into tiny holes in your live rock if threatened. Taking advantage of this trait, the hobbyist can poke a suspected Aiptasia anemone with a probe and observe its reaction. If it rapidly pulls itself downward (as opposed to folding in on itself), it’s likely an Aiptasia anemone.

Which Anemone is it?

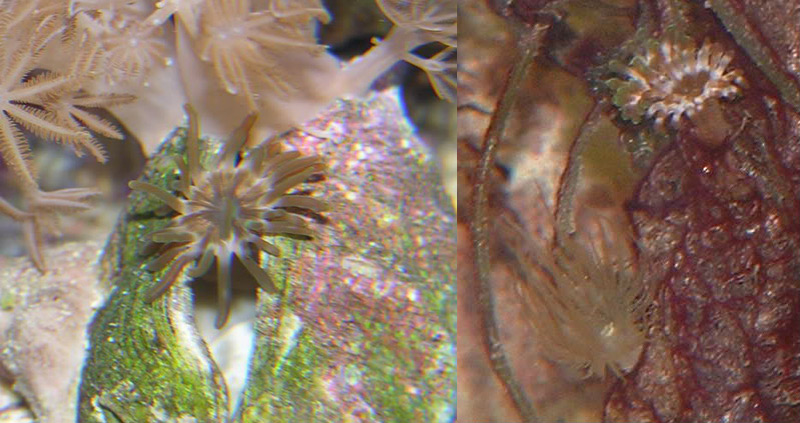

There are two main anemone hitchhikers that the saltwater aquarist is likely to encounter. The first is the Aiptasia anemone; the second is the Majano anemone (Anemonia majano, formerly referred to as Majano anemone). It is important to distinguish between the two anemones because remedies for an Aiptasia infestation will not work as effectively (or at all) with the Majano anemone.

The Majano anemone is also considered a pest and is equally capable of outcompeting and overwhelming a reef tank. Like the Aiptasia anemone, it has a pedal column with a sticky foot that is used to attach itself to the rock surface and an oral disc surrounded by tentacles. The color is typically greenish-brown to tan, with the tentacles having white or light tips. This anemone can grow up to 3 cm (1.5 in) in diameter.

The main difference between the Majano anemone and Aiptasia is that the tentacles of Aiptasia are typically slender and very pointed at the tips, while the Majano anemone has stubby tentacles that are often bulbous at the tips.

The photos above demonstrate this difference. The image shows a close-up of a Majano anemone in the upper-right and Aiptasia in the lower-left. Notice the difference in the shape and size of the tentacles.

The Biology of a Pest

| Taxonomy/Classification: | |

|---|---|

| Phylum | Cnidaria |

| Class | Anthozoa |

| Order | Actiniaria |

| Family | Aiptasiidae |

| Genus | Aiptasia |

The Aiptasia genus (first described by J. L. Chr. Gravenhorst in 1831) comprises 17 accepted species, with the most common being:

- Aiptasia pallida: Brown Glass Anemone, Pale Anemone

- Aiptasia pulchella: Glass Anemone

- Aiptasia diaphana: Small Rock Anemone

- Aiptasia mutabilis: Rock Anemone, Trumpet Anemone

Distribution

Members of the Aiptasia genus are found in tropical and subtropical oceans worldwide, including the Western Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean from Bermuda to South America, the Northwestern Pacific east to Hawaii, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Red Sea. Most of the 17 species of Aiptasia are distributed in the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea, with only Aiptasia californica and Aiptasia pulchella reported in the Pacific Ocean.

Habitat

Aiptasia anemones are found in shallow waters along protected coasts and along intertidal rocky or mangrove-lined shorelines, as well as in deep-water areas with good to strong tidal flows. They will also form dense colonies in areas of shallow water, sometimes so dense they look like solid sheets. Aiptasia anemones are also found alone attached to rubble, mangrove roots, dead corals, and other hard substrates. Aiptasia species are able to withstand a relatively wide range of salinities, light levels, and other water quality conditions, which makes them hard to control. All species of Aiptasia are commonly found with live rock that may be imported to your saltwater aquarium.

Morphology

Cnidarian species are found in one of two body forms: the polyp or the medusa. In the case of Aiptasia, the body form is the polyp, with no medusa stage. The body is composed of a pedal disc with which Aiptasia attaches to the substrate, a smooth and elongated body column, and an oral disc that bears the mouth and long, stinging tentacles.

Like all members of the phylum Cnidaria, all Aiptasia species utilize a tissue-level organization, meaning they possess specialized cellular collections that perform biological functions and lack structured organs and organ systems. Aiptasia are composed of two cell layers: an epidermis and a gastrodermis. The two cell layers are cemented together by an acellular matrix known as mesoglea. The gastrovascular cavity of Aiptasia is partially subdivided by radially arranged rays (or partitions) containing ray-like acontia and gonads along their inner edge.

Symbiotic single-celled dinoflagellate algae, zooxanthellae, are found within the gastrodermal cells. Both the acontia and epidermis harbor cnidocyte stinging cells.

Behavior

Aiptasia swim by ciliary action in spirals or by crawling on their side, progressing at about 4 cm per hour. This video shows an Aiptasia swimming to get away from an attacker. This is a rare action and is not commonly seen. Otherwise, the Aiptasia anemone moves by pushing the pedal disc forward by contraction of circular muscles, shortening the trunk by contraction of longitudinal septal muscles, and pulling the oral disc along after. Sometimes Aiptasia will simply disconnect and float around in your aquarium until they find a better spot to live.

Feeding Habits

Aiptasia contain zooxanthellae, or symbiotic dinoflagellate algae, which produce oxygen and fix carbon by photosynthesis. Much of the carbon fixed is released to the anemone, aiding in its energy needs, while the Aiptasia, in turn, supplies the algae with nitrogen and phosphorus in the form of ammonia waste byproducts. Anemones also feed on zooplankton as well as filtering nutrients and other plankton from the water column.

In your home aquarium, Aiptasia anemones will happily eat fish food and coral foods when available. Many times, Aiptasia can be found growing in an overflow because they can easily take in fish food that moves into the overflow with the circulating tank water. Care should be exercised when feeding your aquarium livestock to avoid overfeeding, which can fuel Aiptasia population growth.

Reproduction

Reproduction is both sexual and asexual.

Asexual

Aiptasia reproduce asexually by pedal laceration. Small masses of cells are pinched or torn off the margins of the pedal disc, forming small buds. These grow slowly into buds, and within a week or two after completely separating from the foot, the bud develops a mouth and small tentacles and begins to feed on its own. Some of these clones will regenerate and be distributed in the water column to colonize other locations. Additionally, Aiptasia demonstrates a preferential tolerance to its own clones and will not sting them. This allows large groupings of Aiptasia clones to form as a result of asexual reproduction.

Unlike some cnidarians, Aiptasia are extremely successful in generating or regenerating an entire animal from a single cell. This is why physical removal is so difficult to perform successfully.

Aiptasia increase asexual reproductive basal laceration during times of extreme stress, such as low oxygen, decreased circulation during power failures, low lighting situations, attack by predators, or when the aquarist attempts physical or chemical methods of removal.

Sexual

While there is little scientific documentation on sexual reproduction within Aiptasia, general observations indicate that sexual reproduction may occur in two forms.

In the case of the well-studied Aiptasia pallida and Aiptasia pulchella, individuals are dioecious, meaning that individuals are of separate sexes. During spawning, anemones release their gametes into the water, where fertilization occurs. The resulting zygote becomes a free-swimming planula larva, which eventually settles onto a suitable substrate and undergoes metamorphosis to become a small polyp. Newly produced larvae are aposymbiotic, meaning they do not contain symbionts. The larvae or newly settled polyps acquire symbiotic algae from the environment.

In certain species of Aiptasia, fertilization may be internal, in the coelenteron. Male gametes are released from male Aiptasia into the water column. These gametes are non-buoyant and settle to fertilize the female gametes within other Aiptasia. These gametes develop internally to the Aiptasia into planulae larvae, receiving nourishment from the hosting anemone. When conditions are optimal (light and nutrients are high) or during physical attack (as when an aquarist is attempting to remove them), these larvae are released into the water column to start growing and colonizing other parts of the reef.

Methods for Removal

There are many methods that have been developed for Aiptasia removal. Some methods involve simply scraping them off, while others burn them off live rock that can be removed from the aquarium. Below is a list of the more common (and safe) methods of dealing with Aiptasia. Each solution has its advantages and disadvantages and may not be right for your situation or compatible with your aquarium livestock. Read each method of Aiptasia anemone removal carefully before deciding which approach to pursue.

Physical Removal

While for many this may be their first reaction, extreme care should be used in this method. When attempting to remove Aiptasia anemones physically, every piece must be removed, as leaving behind a small piece of Aiptasia will regenerate another. You cannot simply cut them up or brush them off. Aiptasia can reproduce by pedal laceration or being broken up, which only serves to help them multiply much more quickly.

If physical removal is attempted, it is also important that the remains of the Aiptasia be removed from the tank to prevent decomposition from introducing excess nutrients into the aquarium water. A Majano wand is newer in the arena of Aiptasia control and removal. While it may work on Majano anemones, it does not work well on Aiptasia anemones. When the Aiptasia breaks up, the small pieces of tissue regenerate new Aiptasia. Also, if the anemone is not fully killed, it will go into survival mode, reproducing quickly.

Strengths

This method is cheap.

Weaknesses

This method is often a waste of time. It is nearly impossible to scrape every last piece of an Aiptasia off from the live rock. Additionally, Aiptasia are often anchored in small crevices within the rock into which they retract the moment you begin scraping. This also makes it impossible to remove every last piece of the organism, and each piece left will undoubtedly grow a new complete Aiptasia.

Under such stress, certain species of Aiptasia will go into reproduction mode and release their planulae (offspring) into the water column, which will settle in the aquarium and grow new Aiptasia anemones.

Chemical Removal

Chemical removal involves the application of a chemical agent onto or injecting it into the Aiptasia. There are many concoctions that have been put forth as “cures” for Aiptasia, and each works to varying degrees. But it is not uncommon for these treatments to actually make your Aiptasia spread even worse in your aquarium. Use these products with caution.

The important point to note with chemical removal is that most of the “remedies” introduce chemicals into your reef aquarium and may negatively alter your tank chemistry, especially if applied in large doses.

These chemical treatments are harmful to all life, despite the claims. If the chemicals are injected or applied to a live coral or any other living animal in your aquarium, it will harm it, so care must be taken when applying these chemicals. Additionally, many of these chemical solutions are harmful to you! So, if you choose to implement any of these methods, make sure you protect yourself by wearing appropriate gloves and eye/face protection, and if they contact your skin, eyes, or are ingested, contact your local poison control center immediately.

When using chemical treatments, always be prepared for large water changes in the event that the treatment you choose results in the poisoning of your aquarium inhabitants. Sufficient saltwater should be on hand to allow for at least a 50% water change if negative effects are noticed with any of your aquarium inhabitants. Also, major water parameters should be tested before and after treatment to ensure that there are no adverse effects on water quality.

Household (or Reef-hold) Remedies

These remedies are concocted from typical chemicals around the home or reef.

Bottled Lemon Juice Concentrate – This treatment relies on the weak acetic acid within the lemon juice to kill the Aiptasia. The lemon juice is injected into the Aiptasia, allowing the acid to kill it from the inside out. Care should be used, as the lemon juice can irritate coral tissue if inadvertently applied to it.

Results: If injected properly, this method has a relatively high kill rate, but injecting inside the anemone is extremely difficult, and often portions of the anemone remain to regrow, making the condition worse in your aquarium.

Calcium Hydroxide – Injecting Aiptasia with calcium hydroxide (often referred to as Kalkwasser, Kalk, or Pickling Lime) in a concentrated solution is one of the most common chemical methods used. A derivative of this solution involves mixing the calcium hydroxide (a powder) with just enough water to make a thick paste, like the consistency of toothpaste. The paste is then applied over the Aiptasia using a turkey baster, turkey injector, or simply spread with a blunt applicator. The whole Aiptasia anemone needs to be covered to avoid leaving a living piece of tissue to regenerate another Aiptasia.

Important: Concentrated calcium hydroxide is a medium-strength base and will kill or severely injure anything it is applied to. Also, attempting to apply this solution to too many Aiptasia at once may have a negative effect on the pH and alkalinity within your tank.

Results: This method works but is not very effective unless done properly. The injection of the Kalk is less effective than the application of the paste; however, it is very difficult to get the paste to cover the anemone, especially in tanks with moderate to high water flow or where the anemone is attached inside a rock crevice or is not attached to a horizontal surface.

Sodium Hydroxide – Also called lye or caustic soda, sodium hydroxide is a principal agent in oven cleaners.

| WARNING! – Solid sodium hydroxide or solutions of sodium hydroxide will cause chemical burns, permanent injury, or scarring if it contacts unprotected human or animal tissue. It will cause blindness if it contacts the eye. Protective equipment such as rubber gloves, safety clothing, and eye protection should always be used when handling the material or its solutions. Dissolution of sodium hydroxide is highly exothermic, and the resulting heat may cause heat burns or ignite flammables. It also produces heat when reacted with acids. It is corrosive to glass and some metals. Keep away from aluminum. |

In this remedy, the powdered sodium hydroxide is mixed with water to form a paste, which is then applied to the Aiptasia.

Results: This is a biocide and will kill Aiptasia if applied correctly. General results indicate a high kill rate for exposed anemones, with success rates dropping to 50% where Aiptasia is anchored in a crevice in the rock or on vertical surfaces.

Hot Boiling Water – This method involves “blasting” the anemone with boiling water from a syringe. It does not work very well, and your chances are slim of it helping to get rid of the Aiptasia.

Other Remedies – There are numerous other remedies (such as hot sauce, strong acids, boiling Kalk, or hydrogen peroxide) touted as “successful” against Aiptasia. Most of these have very limited success rates or are too dangerous (both to you and your aquarium inhabitants) to mention here.

Commercial Chemical Remedies

There are several commercially available treatments for Aiptasia. All of these require direct application to the Aiptasia, either by injection into the body of the anemone or by “feeding” the anemone. The latter method requires application of the chemical to the oral disc of the anemone.

Some manufactured chemicals include:

- Red Sea Aiptasia-X™

- Blue Life Aiptasia Control

- Joe’s Juice

- Chem-Marin Stop-Aiptasia

- Aiptasia-Away™

- Tropic Marin Elimi-Aiptas

It should be noted that these products are typically a derivative of one of the above-mentioned solutions, often containing a caustic chemical to kill the Aiptasia together with additives that either encourage the Aiptasia to feed (thus ingesting the chemical) or that help the product adhere to the anemone (like a glue). In situations where the Aiptasia is easily reached, these chemicals may have good results. However, in hard-to-reach areas of your aquarium, under corals, or where the Aiptasia can withdraw into a crevice, their effectiveness diminishes markedly.

Careful research should be done to ascertain the contents of any commercial product used. They will affect your tank parameters and will harm any other life they come in contact with within your aquarium.

Overall Strengths

These methods are relatively simple and cheap if only a few Aiptasia are present, and many have reported some success. Application is a bit tricky, especially if an Aiptasia is not sitting on an easily accessible horizontal surface. Chemical treatments make the most sense when treating a very small number of Aiptasia in a controlled area (as in a quarantine tank) where the Aiptasia can be easily reached.

Overall Weaknesses

First, these methods introduce chemicals into your system that will affect the stability of your aquarium. Whether the solution you choose is an acid (like lemon juice) or a strong base (like sodium hydroxide), it will have an effect on your aquarium water pH at the minimum. The amount of this effect is dependent on the amount of chemical used as well as the size of the aquarium. Additionally, these chemicals add organic material (either directly or from the remains of the Aiptasia) to your water that will result in an increase in nutrients.

Injecting Aiptasia is much easier said than done. The moment the needle touches the anemone, it will retract into the rock. It can also be difficult to reach many of the Aiptasia anemones growing on the rockwork without removing the rock they are attached to.

Typically, the injection is insufficient to completely kill every little piece of the Aiptasia, resulting in more Aiptasia growing from the remains of those treated. Some of these treatments have a “blast” effect that results in the Aiptasia fragmenting and leaving living pieces free to float and settle elsewhere in the aquarium.

Additionally, under such stress, certain species of Aiptasia will release their planulae (offspring) into the water column, which will settle on the rockwork and grow new Aiptasia. It should also be noted that some of the chemicals that claim to rid your aquarium of Aiptasia do not actually work or contain very harmful compounds. You need to research specific brands if you decide to use a commercially available product.

There have also been reports of sudden coral deaths associated with the use of chemical means of removal. While the exact cause of these sudden deaths is currently unknown, some have theorized that it may be related to the sudden release of dopamine and serotonin, which can be found in both the tentacles and the body of the Aiptasia. Dopamine affects the central nervous system, and serotonin affects brain activity and balance. The purpose or function of these chemicals in Aiptasia is currently unknown.

Natural Remedies

All pests have a natural predator to maintain balance. This is true of Aiptasia anemones as well. There is a whole spectrum of animals that eat Aiptasia anemones to varying degrees. It should be noted that only one of these predators (the Berghia nudibranch, now classified as Aeolidiella stephanieae) has specifically evolved to eat only Aiptasia. As such, it is the most motivated predator available to rid your tank of this pest. All other predators listed below have shown an affinity for Aiptasia, but typically it is a meal of last resort. When selecting a natural predator of Aiptasia, it is important to match its habitat requirements to those of your particular reef environment. Not all predators are suited for your aquarium’s environment. Failure to use care in this selection could be detrimental to either the predator added to your tank or your current tank inhabitants (or both).

Nudibranchs

The Berghia nudibranch, from the Florida Keys region of the West Atlantic Ocean (formerly known as Berghia verrucicornis and recently reclassified as Aeolidiella stephanieae due to morphological and genetic distinctions), is by far the most popular choice because it is 100% safe and effective when used and cared for properly. Berghia eat only Aiptasia anemones, nothing else. Lacking Aiptasia to consume, they will die, thus they are the most motivated Aiptasia predator. While the smallest of the Aiptasia predators, they are the most efficient, consuming the entire anemone, including the entire pedal disc and any planulae within. They can crawl all over your tank to eat the Aiptasia you see and the ones you do not see. If acclimated and added to a well-maintained tank, they are hardy invertebrates. Occasionally, they reproduce to help speed up Aiptasia eradication.

Weaknesses: It takes weeks to months for Berghia to eat heavy Aiptasia infestations, especially if you do not get the correct number of Berghia nudibranchs for the Aiptasia population in your aquarium. If the Berghia are not at least 1/4 inch, they should be maintained in a small tank or a container of at least 1 gallon of water until they grow larger before they are placed in a display aquarium.

Predators: Possibly peppermint shrimp, nocturnal scavenging fish, including fish in the Coris wrasse family; to a lesser extent, underfed large brittle or serpent stars, Emerald and Sally Lightfoot crabs, and coral-banded shrimp.

Other Prey: None

Hermit Crabs

There are a few hermit crabs that have been reported eating Aiptasia. However, these crabs are not reef-safe. One such hermit crab is the White Spotted Hermit Crab (Dardanus megistos), which has been reported to consume Aiptasia. However, this crab is extremely aggressive to other tank mates (including other hermit crabs). Reaching an adult size of 8 inches, this crab is seldom an appropriate addition to most reef aquariums.

NOTE: Dardanus megistos is sometimes referred to as the Red-Legged Hermit. This is not the same as the Red-Legged Hermit Crab commonly sold, which is a different species, Clibanarius sp.

Weaknesses: Crabs are opportunistic feeders. They will eat what is available and will always choose more tasty food over Aiptasia. Thus, in aquariums with excess feeding or other readily available feeding opportunities, these crabs will tend to ignore the Aiptasia.

Predators: This crab has few predators within the common reef tank due to its aggressiveness and large size. However, some aggressive tank mates may prey on this crab, including some species of eels.

Other Prey: It is known to feed on tube worms, mollusks, some corals, and fish. It will also eat algae. It will attack and kill fish, snails, and other hermit crabs (even its own species).

Peppermint Shrimp

The Peppermint Shrimp (Lysmata wurdemanni) has mixed reports concerning Aiptasia consumption. Be aware that there is some confusion in the trade regarding this species and other Lysmata species. These other species are not known to eat Aiptasia, so be careful when purchasing. Also, the Camelback Shrimp (Rhynchocinetes uritai) is often misidentified or misrepresented and sold as a Peppermint Shrimp. Camelback Shrimp do not eat Aiptasia.

Weaknesses: Shrimp are also opportunistic feeders. They will eat what is available and will always choose more tasty food over Aiptasia (often stealing food directly from the mouths of corals and other ornamental anemones). Thus, in tanks with excess feeding or other readily available feeding opportunities, these shrimp will tend to ignore the Aiptasia. Reports of success with Aiptasia control are completely mixed, which may be due to the mix-up in species designation between other members of the Lysmata genus or due to the availability of other food sources. Peppermint Shrimp will also most likely not attack large Aiptasia (anything over an inch tall). In these cases, it may be necessary to physically remove large specimens and allow the shrimp to “clean up” those that reemerge as smaller anemones.

Reports of Peppermint Shrimp destroying corals and even ornamental anemones are quite common. Being a nocturnal feeder, this damage often goes unnoticed until significant damage has been done. If you have expensive corals in your tank, especially large-polyp stony corals, you may not want to trust Peppermint Shrimp.

Predators: More aggressive tank mates may prey on this shrimp, including some species of wrasse.

Other Prey: Shrimp are opportunistic scavengers and will eat anything available.

NOTE: If you tried Peppermint Shrimp and didn’t get the results you expected, catching them can be easy using a simple DIY Shrimp Trap.

Fish

There are several fish (listed below) that have been reported to consume Aiptasia. While not the major component of their diets (nor the preferred one), they will graze on the anemone. Care should be taken in selecting a fish, as many of these are not reef-safe and have been reported to nibble on coral polyps.

One special note on the Copperband Butterflyfish (Chelmon rostratus). This fish is extremely difficult to acclimate to a new tank. Most specimens purchased are diseased and die shortly after purchase. In addition, they are shy, methodical eaters that can be easily bullied by more aggressive tank mates, resulting in their starvation and eventual death.

- Klein’s Butterflyfish (Chaetodon kleinii)

- Raccoon Butterflyfish (Chaetodon lunula)

- Copperband Butterflyfish (Chelmon rostratus)

- Saddled Butterflyfish (Chaetodon ephippium)

- Threadfin Butterflyfish (Chaetodon auriga)

- Hawaiian Butterflyfish (Chaetodon tinkeri)

- Banded Butterflyfish (Chaetodon striatus)

- Bristle-Tail Filefish (Acreichthys tomentosus)

Weaknesses: These fish are not reef-safe and may nibble on or attack certain corals, clams, or ornamental anemones. Care should be taken in researching each fish to determine its dietary needs, compatibility with other tank mates, and degree to which it is compatible with corals within the tank.

Most of the fish suggested will browse on various types of soft and stony corals, zoanthids, sea mats, and polyps.

Many of the animals listed naturally feed on various types of both sessile and motile invertebrates, such as other sea anemones, feather dusters and other tube worms, clams, sea urchins, and crustaceans.

Conclusion

Whether you have spotted your first Aiptasia anemone or you’re the unlucky owner of dozens of them, there is hope. There are many options for controlling and removing Aiptasia from your reef aquarium, some being more effective than others.

Aiptasia infestation is a common problem in saltwater aquariums. Chemical control methods can be used, but these should be a last resort, and significant research is required before adding any chemical to your reef aquarium. Natural remedies, such as the Berghia nudibranch (Aeolidiella stephanieae), offer a safer and more sustainable solution. With patience and diligence, these invaders can be overcome.

References

Borneman, E. (2001). Aquarium Corals: Selection, Husbandry, and Natural History. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H. Publications.

Fautin, D. G., & Allen, G. R. (1992). Field Guide to Anemones and Other Cnidarians of the Indo-Pacific. London, UK: Natural History Press.

IUCN. (2025). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2025.1. Retrieved on June 12, 2025, from https://www.iucnredlist.org.

Marine Species Identification Portal. (2025). Retrieved on June 12, 2025, http://species-identification.org.